Words by Silas House

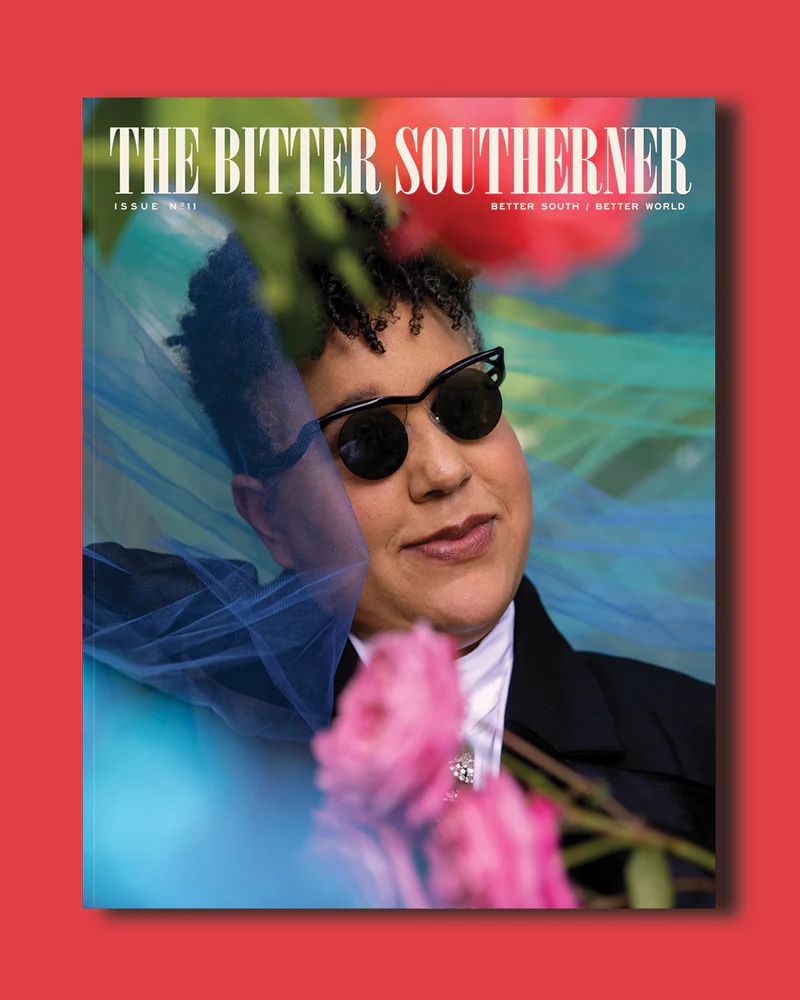

Photos by Carey Neal Gough

July 8, 2025

Near midnight on May 16, a massive tornado left a 60-mile-long scar from Laurel County, Kentucky, to Pulaski County, carving a path so deep and wide across the Daniel Boone National Forest that it can now be seen on satellite imagery. Along the way, winds reached 170 mph, eventually culminating near the small city of London, where it killed 18.

As a young man I carried mail for seven years, often in the community where the deaths and worst devastation occurred. Before that, I went to high school in London. I grew up not far away in this tri-county area of southeastern Kentucky.

Three days after the storm, my daughter and I traveled down home. I had told a few friends we were going and within minutes they donated nearly a thousand dollars to help, so we went shopping and took along tarps, totes, food, water, garbage bags, cleaning supplies, and much more. When we arrived we found Laurel County looking like a war zone. Pictures and videos cannot completely capture the destruction there, and it was hard to see the place I knew so well suffering such pain.

Traffic was backed up for miles, clogged by emergency vehicles and rubberneckers, but we eventually made it to a central command area where the recovery effort was in full motion. When I told a boy in a yellow vest that we had brought supplies, we were first directed to a bright green food truck. Osvaldo and Donna Sierra, along with their children and other family members, had spent the last three days working nearly nonstop to feed burritos, hot dogs, fries, and more to volunteers, storm survivors, and emergency personnel. I had heard about them on social media and had brought along several pounds of ground beef and a case of tortillas. They thanked us profusely although they were the ones who deserved the gratitude. Next we went to the Finley Trailer Park, one of the hardest-hit spots, which became a central donation site where survivors went for food and supplies.

The first person I saw staffing a table was Lu Fields, who describes herself as “a proud transgender woman.” I had met her a couple times before but mostly knew her because she is an equality legend in the region: She’s spent her life fighting for LGBTQ+ rights and other social justice issues. She hurried toward me with arms stretched wide and embraced me. That’s home. To be wanted and welcomed, to feel safe.

“Oh, honey, love your heart,” she said, taking a pile of work gloves from my hands. We were surrounded by other folks who flew into unloading our supplies, stacking them all with a solemn expertise. One of them wore a neon green shirt with Jesus Loves You emblazoned across it. Trucks were being unloaded all around us. An entire wall of bottled water had been erected from donations. A bulldozer pushed the twisted remains of several trailers into a pile behind us, bringing down the scoop to gently tap the mess into some semblance of order. Most everyone was caught up in the business of service, but I saw others who were wandering aimlessly, shock clear in their eyes.

I was overcome with a feeling of being home. I lived near this community until my mid-30s, but I left 16 years ago and now live about 90 minutes north in Lexington. I’ve been homesick ever since. I carry a constant heartache that is perhaps more accurately called timesickness. A longing for the way things used to be in the place where I grew up. The more I think about it, the less I can separate my childhood from that place in the world. They are as tangled as the kudzu vines that thrive there. The past is my first home, the period that shaped me into who I am, the span of years where I felt great love and safety.

Of course, it’s easy to look back with nostalgia and oversimplify the past. We tend to fixate on the good things when we think of home. But I remember the violence: My uncle was murdered when I was 11; my father’s PTSD was a smoldering incendiary in our home. My aunt, whom I adored, often cried while she drank coffee and smoked her Winston Lights. “It’s just the blues,” she’d say, but even as a child I knew it was more than that. I recall the way it felt to always be on the outside looking in — the sissified boy with glasses and thin arms who always had his nose buried in a book. I was made fun of for all of those things, and more.

Home was a mixture of great love and deep sadness, periods of calm punctuated by moments of intense pain or passionate joy. Over the past decade, most of the people who have embodied home for me have either died or been mesmerized by a political regime I cannot abide. In either case, they are gone from me.

Often I go down home with some trepidation. In the last election, 84 percent of the population there voted for an administration I find reprehensible. It is hard for me to rectify this allegiance with people I have known to be so kind, loving, and generous. Yes, I witnessed a lot of bigotry growing up there, but most of us do, no matter where we’re from. I have always been more conscious of it because it happens in my home, where I should feel safe and welcomed. So even though I love my homeplace to my bones I don’t always feel like it loves me as a progressive, gay man.

Somehow, though, and against my will, this makes me love the place even more. Those ridges and pastures, the mist rising like ghosts from the caves and crevices. The little creek where we played runs in my veins as well as through those woods where I grew up with glowing mosses and lazing ferns. My elementary school, where my seventh-grade teacher first showed me the power of poetry. My high school where I first felt the bloom of romantic love and got into my first fist fight. All the homes along the winding roads where I drove as a wild teenager and later as a tired mail carrier. Most of all, the people. In my mind’s eye I see their working hands, I see the smiles on their faces, I see them stretching out their arms to embrace me without hesitation, the way Lu Fields did in the middle of all that loss. I think of the 16 percent who voted against a treacherous president spouting constant, divisive vitriol and I love them even more, knowing they are on the front lines, resisting. They are braver than me. I live in a blue dot now, where I feel safer and more welcomed, but they’re there, fighting back.

Before we left the half-ruined trailer park that day, I noticed a group of folks sitting in a circle of folding chairs, drinking coffee and chatting. They were taking a break from the work and trauma together, some of them laughing, a couple of them smoking, a few crying, all of them chattering away. Few things melt me quicker than hearing the accents, the cadences, the colloquialisms of home, and they were in abundance in this gathering. They were together among the chaos. Where I’m from, we work hard but then we sit down and talk to each other. Back home we call this “visiting.” Others might call it “checking in on each other” or “taking a breath together.” It’s just about being connected, being present with each other. Seeing one another.

This took me rushing back to the porches and yards of my youth. Home.

When people have lost everything, when they are suffering, when they need you — none of us should care how any of them voted. I don’t. The culture of my homeplace taught me to love others without judgment, a tenet that many of the loudest voices in the public arena do not want us to practice because we are more easily controlled when we are divided. I will not let them take my love away any more than I will let them take my joy. I will be no one’s doormat and I will never make myself unsafe but I will give everyone grace, even those who deny it to me and so many others. I will fight back. I will resist, but I will refuse to hate anyone. I will look for the open arms of acceptance, and they will be there, somewhere in the crowd, waiting for me.

That’s what I was taught where I am from, back home, in that time and place. That’s the part of it I always long for, and hope blooms in my chest any time I see that some semblance of it still lives there. We all need that right now.

— Silas House

Silas House is the New York Times and USA Today bestselling author of seven novels. He currently serves as the poet laureate of Kentucky and as the National Endowment for the Humanities Chair at Berea College. In 2022 he was given the Duggins Prize, the largest award for an LGBTQ writer in the nation.

Carey Neal Gough is a photographer living and working in Lexington, Kentucky. Her work explores the intersection of the natural world, memory, and emotion — where dream and reality sit side by side. She photographs in places where time, weather, and wildness are the dominant forces, offering a quiet reminder that we are not separate from the natural world, but of it. In addition to her freelance practice, she is a part-time instructor at the University of Kentucky.