Visitors to Nashville’s Hatch Show Print often ask the printers why they don’t use faster, modern technology to make their iconic posters. But this 138-year-old business — whose work says “Nashville” to the whole world — doggedly sticks with a 578-year-old printing method, letterpress. As a result, Hatch is to country music as Gutenberg was to the Bible.

Story by Jennifer Justus | Photographs by Abigail Bobo

Two weeks after the 2016 presidential election, a team of artists dressed in blue jumpsuits descended upon one of Nashville's most popular restaurants. Along one wall, people from a local print shop called Isle of Printing arranged thousands of cans wrapped in colorful paper into a 50-foot-long public art message: two pixelated-looking, cartoon characters sharing a one-word balloon that read "Let's Talk."

It was a modern art project for modern times. But those eye-catching labels were printed in the most old-fashioned way: letterpress, the printing method that goes all the way back to Gutenberg himself.

Meanwhile that month, across town at the Ryman Auditorium, guests arrived early to see country artist Kacey Musgraves and to snag a limited-edition show poster made in the same method. And just south of Nashville at Middle Tennessee State University, Kathleen O’Connell showed students how to transfer ink onto paper using antique machines and movable type. The name of the class: Letterpress I.

Nashville’s most famous and longest running letterpress print shop, Hatch Show Print, opened its doors in 1879, the same year Thomas Edison demonstrated the first incandescent light bulb. And Nashville was especially suited for a letterpress operation like Hatch. The print shop had a front row seat to the music business, and the posters it printed to advertise concerts ensured the company’s success.

Over the years, Hatch helped the trade of letterpress printing become an art form. And through its posters, it visually articulated the music industry. Hatch’s posters build a bridge between the humanity of country music and high art, in an accessible way for all, says Jennifer Cole of the Metro Nashville Arts Commission.

The stamp of Hatch Show Print can still be seen and felt today – both across the city and beyond in the community of letterpress printers.

Letterpress is slow. It’s physical. It’s gritty. But like a vinyl record, Hatch’s letterpress lends an analog realness to a digital world that is too often shiny and perfect. And while the majority of images we encounter today are viewed on computers or smartphones, every handmade print at Hatch is an individual piece that carries its own story and the physical marks of a craftsman. Letterpress isn’t something you view through glass; it’s something you can smell and feel.

“It’s perfectly imperfect,” says O’Connell. “It’s really beautiful because you’re seeing this history. It has character to it.”

Over its years in operation, Hatch has spawned artists who have the work ethic to create approachable, commercial art that’s inspired the look of Nashville itself. New type isn’t manufactured at Hatch, because it aims to preserve the look and feel of the place. So designers must work with what’s on hand, which can’t be stretched or squished on the page. They force creativity through limitation, like a songwriter working with just three chords and a handful of words.

“In a computer, you can resize things. And if you want a thousand A’s, you just keep holding the button down,” says Bryce McCloud, who worked at Hatch before founding Isle of Printing. “I feel like that push and pull really makes you stretch yourself creatively. A lot of times (in letterpress), your first answer just isn’t possible, so you have to go with Answer F.”

Being at Hatch Show Print when the old presses run sounds like a 1950s-era newsroom full of manual typewriters that’s been crammed into a bowling alley. Clickety-clacks, punctuated by thumps and thuds.

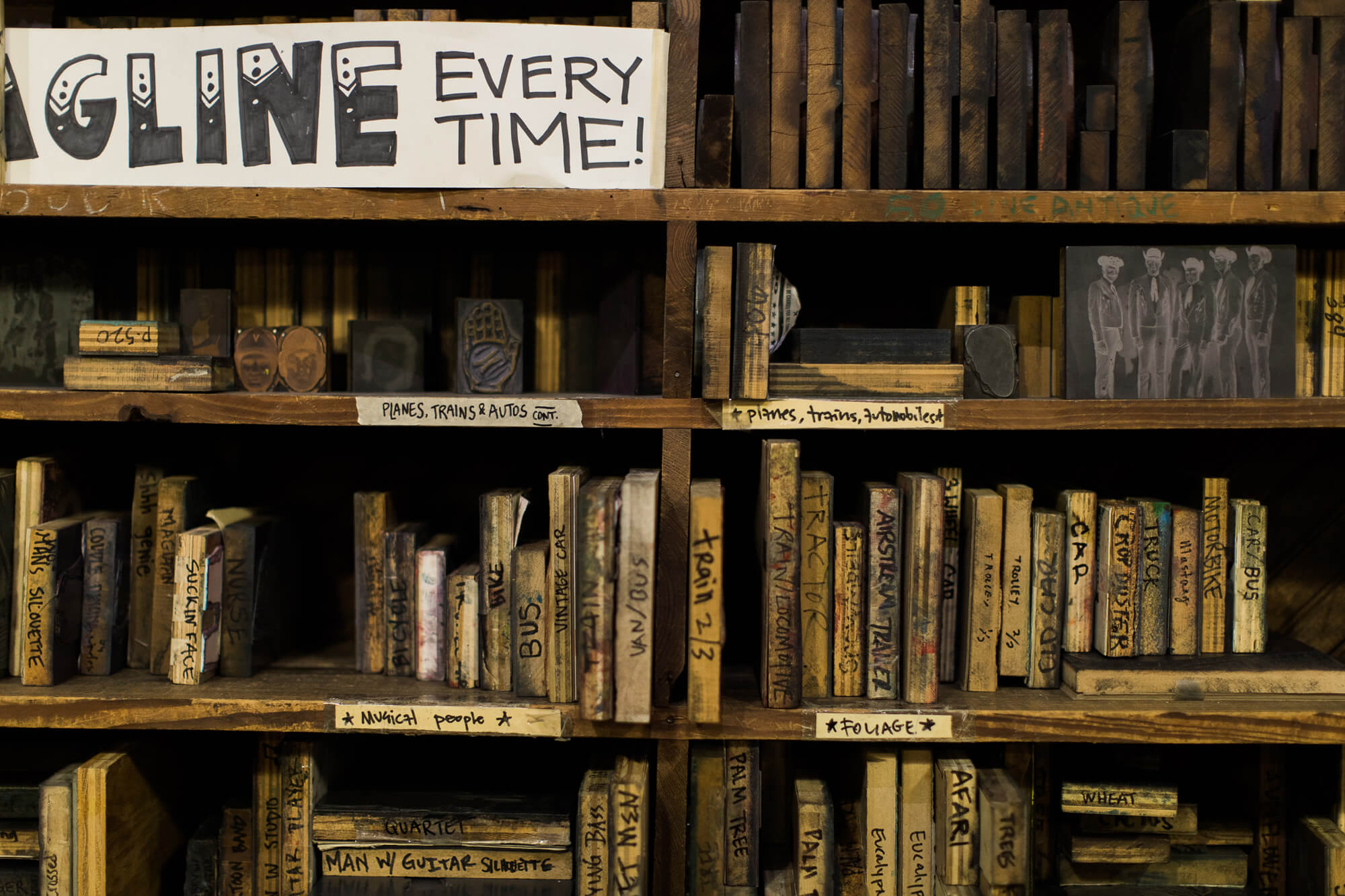

The air carries a faint chemical smell from ink and mineral spirits, which Hatch’s printers use to clean the presses. The walls are lined with wooden blocks of type, stacked to the ceiling. The type’s dark, worn appearance and the clunky antique presses give the place an organic feel. The shop has the cluttered but mostly organized look of a toolshed, because the employees must save everything for archiving purposes — every proof page and scrap of paper with scribbled notes, every carving and poster. They save bits of ink in old yogurt cups, just in case they need to match the color for another job. And some things they save just to be cheeky, like a few hairs from Maow, the yellow and white cat who lives at the shop, taped to a filing cabinet.

And while you can find the work of Hatch Show Print on a band’s merch table at the Ryman these days, that wasn’t always part of the plan. Designs were created instead to stretch across barns to “sell or tell” you while you bounced down the road in a Model T or worked in the fields nearby. They conveyed basic information in a pleasing way about tent shows, auctions and boxing matches. Hatch’s first job, a handbill, advertised a show of a different sort — a talk by an abolitionist preacher named Henry Ward Beecher, the brother of “Uncle Tom’s Cabin” author Harriet Beecher Stowe.

Yet even as Hatch’s reason for being has evolved, the shop’s way of existing hasn’t. Letterpress printing is still hand-carved letters and images (some of them nicked from 100 years of wear) pressed into paper with ink. Colors must be applied one at a time with 24 hours of drying time in between, and every piece is hand-pulled off the press.

Hatch Print Shop Manager Celene Aubry says the company’s old-fashioned ways can confound some guests. When Vanderbilt University’s Owen School of Business sends students to Hatch on field trips, one student will inevitably ask, “You know there’s a faster way to do this, right?”

But Hatch believes the slow way is best. Orders for jobs at Hatch are not accepted by email — just snail mail, fax, or human delivery. Designers hunch over drafting tables or presses, rather than computers, to do their work. And when standing by the presses, they are like the barbecue pitmasters of the design world, physically tending to their masterpieces in time-consuming work learned and passed down from old-timers, who probably considered their labor more of a trade. These days, the process gets its due as art.

A scan of the room at Hatch is like a history lesson in music and entertainment as posters cover every open wall surface — WSM radio ads, tent-show posters, trippy Flaming Lips designs beside vintage Dolly Parton. Hatch completes about 550 jobs a year (about 75 percent of those are show posters). Eight full-time designer-printers handle the jobs from start to finish, from dealing with the client to designing and printing. And everyone who has worked at Hatch has a story — or several — about their favorites.

The largest order, for example, came through in 1999 from the Red Hot Chili Peppers, who wanted 57,000 posters to promote a world tour sponsored by Rolling Rock beer. In 1948, Hatch made enough posters for Roy Acuff’s run for governor (he didn’t win) to buy its neon sign out front. But probably the most famous job came from Elvis Presley’s camp. Hatch printed his first show poster ever, a run of just 100, which made the pages of LIFE magazine in 1956. A photographer captured a preacher in Florida holding up the poster while railing against rock-and-roll’s sins. A poster for Hank Williams, which didn’t have time to dry before he headed out on tour, ended up on the seat of his white pants after he plopped down on it in the backseat of his Cadillac.

All of those jobs were printed essentially with the same method even though they can look vastly different.

“Nothing is digital here. We don’t have our type scanned. We don’t have our images scanned. All of this imagery originates here and becomes part of our collection,” Aubry says, showing a wall of shelves labeled with names like “planes, trains, automobiles,” “animals,” and “hands.” A photoplate of Robert Plant circa 1970 might sit next to Smokey Robinson and the Miracles, who sit next to a Vanderbilt football player in a leather helmet.

“It’s part of the fun in being in a historic shop,” she says. “We pull designs for posters today that were made over 100 years ago.”

William T. Hatch came to Nashville in 1875 as a printer — and a preacher.

The city’s plethora of churches and print shops (it ranked among the top five largest printing cities at the time) surely called to him. So, he moved to town from Indiana in the same year Albert Einstein was born.

Though Hatch quickly made his mark printing a weekly business newspaper, he died a couple years after arriving in Nashville. His sons, Charles and Herbert, carried on the family business by opening their own shop at just 27 and 25 years old, respectively. Legend has it they worked from the basement of the Nashville Banner newspaper building, where Charles had been briefly employed. The brothers might have bought a portion of the Banner’s letterpress printing department, as that technology was already fading in favor of faster offset lithography for newspaper printing. Early work advertised tent shows that arrived in Nashville in caravans, like Silas Green from New Orleans and Rabbit Foot Minstrels. They also made show prints for vaudeville and motion pictures, as well as for businesses and people of the community.

After radio was invented in 1920, entertainment began to change. The Grand Ole Opry came along in 1925 on WSM and reached about 30 states by the 1930s.

“The music they were playing became America’s music. The artists who appeared on the Grand Ole Opry — Bill Monroe, Hank Williams, Minnie Pearl, all those folks — that gave them a leg up when they could go out on the road and tour,” Aubry says. “Clearly, the Opry itself didn’t need posters to advertise, they had radio. But their entertainers, their stars, needed posters, so they came to Hatch.”

The shop had moved to 4th Avenue at the back doors of the Ryman, and that’s where it stayed from 1923 to 1992. Mai Fulton, the longtime bookkeeper at the shop, could see the Opry performers as they left the auditorium, a coup in her line of work.

“Every Saturday night I would go across the parking lot and collect the accounts from the entertainers. It was the only way you could get money from some of those folks,” she says in “Hatch Show Print: The History of a Great American Poster Shop,” a book by longtime shop manager and artist Jim Sherraden with Elek Horvath and Paul Kingsbury.

The Opry’s heyday — in the 1950s — was the last decade the company was owned by a Hatch family member. Offset printing began growing in popularity, and over the next several years, longtime printers and clients kept Hatch afloat through a series of twists and turns.

“Some folks might have thought [the computer] would have killed a place like this, but the reality is when computers first came out, they had maybe this many fonts,” says Aubry, holding her fingers close together to show a small amount. “And none of them matched the tried and true branding by the folks who had built their brands, like Jack Daniel’s. It brought about a new way of looking at the old collection for a different revenue stream.”

With the Opry off to new digs in 1974 and the Ryman facing the threat of a wrecking ball, Hatch also had to rely on loyal, local customers it had maintained over the years. As customers developed more dependence on computers in the 1970s and 1980s, home entertainment systems also caused a dip in live entertainment. Then, a major turning point at Hatch came in 1984, when Jim Sherraden was hired to tell the shop’s story. He soon took over as manager.

“He was like breath of fresh air,” Aubry says. “Guys that were working here were guys who trained on how to letterpress print, sort of your wash, rinse, repeat: full justification, left to right, top to bottom, black photo plate, red type, that kind of stuff. They were from that era.”

At the time, letterpress printers considered their jobs blue-collar. “A lot of this equipment we use that we’re so reverent about, they were like, ‘whatever,’” McCloud says. “I guess it would be like me fawning over a VCR or something. It was sort of more commonplace to them.”

Sherraden, though, had a different background. He had studied history, languages, and printmaking at Middle Tennessee State University. He saw potential in the shop’s history and hand-carved blocks. If those blocks could be used in a commercial way, the shop could make money by showcasing that artistry. He began to reproduce several of Hatch’s classic images on postcards and also began to restrike historic designs at full poster size from Silas Green ads to WSM posters and advertisements for Airstream trailers.

By the mid-1990s, the Ryman Auditorium had also reopened, booking musicians of all genres to play the venue. Live entertainment had swung back into fashion. But this time around, show posters were less about “selling and telling” and more about commemorating the experience.

McCloud was there to witness the shift. “There was this period where people were all about computers, and then people were like, ‘How about this other beautiful art?’” he says. “People really started to appreciate handcrafted things again.”

Culture had swung through the worlds of computer design and malls and the suburbs and was ready to swing back from that processed world, McCloud says. “Once you didn’t have to letterpress parking tickets, and there were other easier ways to do basic stuff, suddenly letterpress was exotic and unique.”

As technology provided us with information and helped us solve other problems, the experience of an event and a visual representation of it became more interesting. It coincided with the idea that the show poster can be a piece of artwork.

“There was a wave of that in the ’60s in San Francisco,” McCloud says of show posters. “In the mid-’90s, it came back in San Francisco again and spread across the country. Hatch was doing its own brand of it the whole time.”

Meanwhile, Gaylord Opryland, which had owned Hatch from 1986 to 1992, donated the shop to the Country Music Foundation, which also oversees the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum. The gift allowed the shop to do business while protecting its future and its archive.

All the while, Aubry noted that authenticity became something people talked more about more universally.

“As humans I think we’re hardwired for things we can look at and know it was handmade. That deepens our appreciation,” she says. “I think we are hardwired to be active makers instead of passive receivers too, so being able to engage with something whether it’s a vinyl record or a poster or to some degree an actual book.”

A renewed interest in letterpress might be partially nostalgic, McCloud says, but also could be attributed to the beautiful idiosyncrasies in the way the ink lies on the paper in a new way every time.

“As someone who makes it,” he says. “It’s exciting because it’s sort of a surprise every time to make a print.”

Bryce McCloud has been called the Willy Wonka of letterpress. And though he hasn’t worked at Hatch since the early ’00s, he still recalls the dreams he’d have of digging through type trying to match a letter with its family or find the right spot for a rouge period.

“There are thousands of drawers of type at Hatch, and they’re kind of labeled,” he says. “Really, you just have to memorize them all. And there’s only one way to do that — pull them open and look in every single one.”

It’s a task often given to newbies at Hatch to help them learn the shop — “putting away the job,” they call it. In taking a job apart, one learns how it has been built.

But the memories of wandering around with a random T weren’t McCloud’s first experience with letterpress. When he was in junior high, he remembers his uncle’s house started to fill up with letterpress equipment. His uncle had studied industrial technology and worked at the state museum. And it broke his uncle’s heart to see languishing letterpresses carted off to the dump, even if he wasn’t totally sure what to do with them.

“It was literally in his kitchen and everywhere,” McCloud says. “I thought everybody’s uncle had a [print] shop.”

Following his uncle’s influence, McCloud visited Hatch after art school and spoke with Sherraden, who let him hang around before and after shifts at his actual job down the street at the Hard Rock Café. Sweeping led to putting away jobs and picking up knowledge from Sherraden and others.

“There was certainly a 10-year period where if I wasn’t down there every day, I was hanging out with the people at night,” he says, though he did actually work there for a year or so of that time.

McCloud is one of many letterpress artists who found a foundation and jumping off point at Hatch, sometimes by interning or just hanging out.

“Hatch was sort of this beacon on the hill, so we went and spent some time there to learn the craft or hone it,” he says.

Julie Sola learned at Hatch before branching out on her own. For years, she has toured with bands like KISS and Rod Stewart, working in wardrobe, while also working at Hatch. “The minute I got off the bus, I’d go in there and start printing,” she says. “I didn’t know anything until I went there.”

She opened her own shop, Fat Crow Press, and now primarily works out of her home making linoleum prints and books, as well as the occasional show poster, like one she recently made for Third Man Records.

“I still have my blister” from printing the job on a manual letterpress, she says.

For printers who leave places like Hatch, finding their own presses can be part of the hurdle — and the fun. “They’re like classic cars,” Sola says. “They’re so expensive if you find one in good shape. I had mine up on blocks in the backyard forever — like you’d put a car up on blocks — until my studio was built.”

Chris Cheney and Nieves Uhl both worked at Hatch before finding their own equipment and opening Sawtooth Print Shop. They take on lots of letterpress jobs that Hatch doesn’t do, such as invitations and stationery.

Indeed, there is such a large web of letterpress printers in Nashville and beyond today, it could warrant a flow chart, with Hatch as the primary connection point. There is Brad Vetter in Louisville, Mary Sullivan in Nashville, Laura Baisden and Julie Belcher in Knoxville, Kevin Bradley in Los Angeles, and Carl Carbonell in Salt Lake City, among among others.

“When I started (in letterpress), I thought all this was going away,” McCloud says. “I thought it was going to be me and three other crazy people who were too stupid to do anything else, just preserving it like the last wagon-wheel makers. But the opposite of that is happening. My question was, ‘Why does my shop need to exist in Nashville?’ I was using this equipment, which was not modern, but I’m a modern person. So, how can I use this to tell today’s story and honor the past while also pushing it forward? That’s what I try to do in my shop, which hopefully honors the tradition that Hatch represents.”

McCloud now incorporates letterpress into public art projects like the can art at Nashville restaurant Pinewood Social. While it involves an old-fashioned process at its core, it’s probably viewed most often via social media, McCloud says. “I really love public art, and to me, that’s what letterpress and printmaking, printing is — a form of democratic art.”

Hatch and the creative and commercially productive artists it can inspire also have helped shape the city’s aesthetic. McCloud says Nashville probably has more letterpress shops than other cities its size.

And true, letterpress influence can be spotted on street corners as often as it is hung on walls as art. Cole with the Metro Nashville Arts Commission says it helps people participate in art while also providing a space for visual artists to work alongside musicians. It bridges a link, too, between old and new Nashville.

“I do think it has a look,” McCloud says of Nashville. “But I think that’s changing rapidly as people move in.”

But if newcomers are curious, McCloud says, Hatch is there for them as a place to find their way into the culture that helped shaped Nashville’s look and feel to this point.

And for now, the younger generations who grow up near here at least, still seem to soak up some of it through osmosis. O’Connell says her MTSU students come to her letterpress classes with an awareness.

“They’ve seen the work and aesthetic,” she says. “They’ve become familiar with letterpress in a way that most students in other parts of the country haven’t.”

Scarlett Cook might be running out of wall space for show posters at her Memphis home, but on a recent trip to Nashville, she couldn’t help but pick up one more.

“You come on in and get one before they run out,” she said, clutching a rolled up Hatch Show Print poster for the Punch Brothers, the bluegrass supergroup she had come to see.

Cook, 37, knows Hatch makes a limited number of posters for every Ryman Auditorium show. But across the hall at the venue, Cassidy Mahan, 20, of Knoxville, was just starting to build her collection. And she knew nothing of the historic letterpress shop called Hatch.

“I hadn’t planned on getting a poster,” she said, unfurling it to show off an ombre-like fade of pastels on paper from hand-mixed ink. The band’s name stretched across the top in block letters over an image of a traveler with a bindle over his shoulder. It, too, had been hand-carved backward and then pressed into paper with ink. “I thought it was just gorgeous.”

While the two women from opposite ends of the state have varying experiences of Hatch, they both wanted to mark this moment in time with a memento — a piece of art — to remember the music, the people, and place. Hatch can do that for them for about $20 each.

Just as the Punch Brothers’ audience members collect Hatch prints to mark a moment, Aubry says the artists often see their first Hatch posters as a rite of passage. They often want to see the place that makes their prints, too, and learn about the process. So the Hatch crew turned one working letterpress machine into a “celebrity press” that’s covered in autographs — Martha Stewart, Jack White, ZZ Top, Rosanne Cash, Alton Brown, to name a few.

Whether they make it to a telephone pole in Spokane or a merch table in New Zealand, Aubry says Hatch posters express their mantra of preservation through production. Just as the Ryman keeps its history alive by hosting new shows, the process of making posters — and the oil-based inks and mineral spirits that literally keep the wood blocks from rotting — also keep the story of Hatch alive.

But even after all it has promoted and endured, Hatch still remains unknown to many. During a recent tour of the place, offered through the Country Music Hall of Fame and Museum for $18, not one of the nine tourists from various parts of the country had heard of Hatch. And at the start of the tour, a few couldn’t fathom why a company would still make posters in such a slow and old-fashioned way.

Linda Cogdill from Washington, D.C., works at the Smithsonian American Art Museum and regularly sees a mural constructed of old wooden type that hangs there. Because of it, she figured the form of printing was long dead.

But this older way of doing things continues to tell stories in fresh ways as the city and people around it change.

“All of Nashville takes you back as you’re hearing the sounds of the past,” she said, musing on how the old can breathe life into the new. “It’s refreshing.”